The Voynich Manuscript

The Voynich manuscript just might be the most unreadable book in the world. The 500-year-old relic was disocvered in 1912 at a library in Rome and consists of 240 pages of illustrations and writing in a language not known to anyone. Deciphering the text has eluded even the best cryptographers, leading some to dismiss the book as an entertaining but lengthy hoax. But a statistical analysis of the writing shows that the manuscript does seem to follow the basic structure and laws of a working language.

John Baez

January 30, 2005

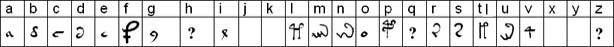

The Voynich manuscript is the most mysterious of all texts. It is seven by ten inches in size, and about 200 pages long. It is made of soft, light-brown vellum. It is written in a flowing cursive script in alphabet that has never been seen elsewhere. Nobody knows what it means. During World War II some of the top military code-breakers in America tried to decipher it, but failed. A professor at the University of Pennsylvania seems to have gone insane trying to figure it out. Though the manuscript was found in Italy, statistical analyses show the text is completely different in character from any European language. Here's a sample page:

It contains pictures of various things, including plants, stars...

... and most strangely of all, nude maidens bathing in what looks like some very elaborate plumbing:

An interesting puzzle, no? Let me tell you a bit more about it.

Its recent history

It seems that in 1912, the book collector Wilfrid M. Voynich found this manuscript in a chest in the Jesuit College at the Villa Mondragone, in Frascati. He bought it from the Jesuits, and gave photographic copies to a number of experts to have it deciphered. None of them succeeded. In 1961, he sold it to a rare book expert in New York named H. P. Kraus for the price of $24,500. Kraus later tried to sell it for $160,000, but could not find a buyer. In 1969, he donated it to Yale University. It is now in the Beinecke Rare Book Library at Yale, with catalogue number MS 408. They say it's "very likely" that the book was given to Emperor Rudolph II of the Holy Roman Emperor by British astrologer John Dee... and indeed, that's one theory, but it's far from certain. The story of the Voynich is long and complicated.

Its earlier history

When Voynich found the manuscript, there was a letter in it!

The letter was written by Johannes Marcus Marci of Cronland, and addressed to Athanasius Kircher. It is dated 1666. It says that the manuscript was bought by Emperor Rudolph II for the princely sum of 600 ducats. In flattering language, Marci asks Kircher to attempt to decipher the manuscript. He mentions Roger Bacon as a possible author, although there is no clear evidence for this.

If you don't know these figures, you probably don't realize how interesting this is. Who are these guys, anyway?

Emperor Rudolph II

Rudolph II (1552-1612) was an emperor of the Holy Roman Empire - which by that time was neither holy, Roman, nor even much of an empire. He moved the imperial court from Vienna to a castle in Prague, in what was then Bohemia. He buried himself in esoteric studies: alchemy, astrology... magico-scientific disciplines of all sorts. Prague became a center for everyone interested in such matters: the infamous British magician John Dee and his henchman Edward Kelley, the monk Giordano Bruno (later burned at the stake for heresy), and even a pair of astrologers by the names of Tycho Brahe and Johannes Kepler. Rudolph II kept a room of curiosities, the Kunstkammer, full of alchemical manuscripts, rhinoceros horns, exotic minerals, scientific instruments, and the like.

In short: the perfect person to buy something like the Voynich Manuscript!

Athanasius Kircher

Athanasius Kircher (~1601 - 1680) was one of the most learned men of his day. He developed an instrument for measuring the magnetic force of the earth, a device for measuring wind speeds, and he designed and built sundials. He studied earthquakes and volcanos. He was an expert on oriental languages, and translated the Emerald Tablet of Hermes, an Arabic alchemical work, into Latin. He also wrote some very popular books on Egyptian antiquities and hieroglyphs. He was the first to correctly conjecture that Coptic was derived from ancient Egyptian. He even received a large gift from the Pope for translating the hieroglyphs on an Egyptian obelisk! When the Rosetta stone was found, quite a bit later, this translation was found to be completely inaccurate. However, during his lifetime he had a reputation for being able to read any text.

In short: the perfect person to decode the Voynich Manuscript!

Roger Bacon

Roger Bacon (1214-1294) was a Franciscan friar and an early advocate of the experimental method. He worked on optics, and at the request of Pope Clement IV he wrote a series of books which amounted to an encyclopedia of science. He also worked on alchemy. He kept much of his work secret from his fellow Franciscans, but nonetheless, in 1278 they imprisoned him on the charge of "suspected novelties" in his teaching. In his Letter on the Secret Works of Art and the Nullity of Magic, he wrote "The man is insane who writes a secret in any other way than one which will conceal it from the vulgar and make it intelligible only with difficulty even to scientific men and earnest students.... Certain persons have achieved concealment by means of letters not then used by their own race or others but arbitrarily invented by themselves."

In short: the perfect person to have written the Voynich Manuscript!

But the story is not so simple....

(To be continued.)

References

The best books to read on the Voynich manuscript are these:- Mary E. D'Imperio, The Voynich Manuscript: An Elegant Enigma, National Security Agency, Fort George G. Meade, Maryland, 1978. Reprinted by Aegean Park Press, Laguna Hills, California, c. 1980.

- Robert S. Brumbaugh, The World's Most Mysterious Manuscript, Weidenfeld and Nicholson, London, 1977. Also Southern Illinois University Press, Carbondale, 1978. (This seems to be out of print.)

- Gary Kennedy and Rob Churchill, The Voynich Manuscript, Orion Press, 2004.

- Jorge Stolfi's Voynich page. Right now this is the master site that takes you to all other Voynich websites!

- Rene Zandbergen's Voynich page. Full of interesting information.

- The Voynich Manuscript Mailing List Headquarters. Run by Jim Gillogly, this has archives of the mailing list where experts discuss the Voynich manuscript - and information on how to subscribe!

- Jim Reeds' Voynich page. This contains a lot of information - in particular, a detailed Voynich bibliography. Both of these are essential reading for the would-be Voynichologist.

- Jim Gillogly's Voynich ftp site. This contains a transcription by Mary Imperio of a large part of the manuscript, Voynich fonts for the PC, and much much more. (Jim Gillogly's ftp site is now defunct, so these links actually take you to Jorge Stolfi's mirror site.)

- World Mysteries: Voynich manuscript webpage. A nice summary of the mystery, with pictures.

- The actual Voynich manuscript. To see the actual thing, you have to go to the Beinecke rare book and manuscript library at Yale; this website gives information on how to do it. You can also purchase a black-and-white photocopy of the manuscript from them! I have one. Yale doesn't make it terribly easy. At present, I think it's much better to buy a color edition...

- The next best thing. You can buy a beautiful French coffee-table edition of the Voynich mansucript from Amazon.fr. It's called Le Code Voynich.

Within that awful volume lies the mystery of mysteries! - Sir Walter Scott

© 2005 John Baez

baez@math.removethis.ucr.andthis.edu

baez@math.removethis.ucr.andthis.edu

******************************************

The Viynich Manuscript decoded?

give examples to show that the code used in the Voynich Manuscript is probably a series of Italian word anagrams written in a fancy embellished script. This code, that has been confusing scholars for nearly a century, is therefore not as complicated as it first appears.

All attempts over the past century to decode this mysterious manuscript have met with failure. This is probably due to the initial error made by Voynich and his followers attributing the authorship of the manuscript to Roger Bacon, the 13th century British scientist, monk and scholar. As I showed in a previous paper on my Website, The Voynich Manuscript, was the author left handed?, Roger Bacon could not have written this manuscript and I suggested that a young (around 8 to 10 years old) Leonardo da Vinci was a likely author. Using this premise I proceeded to consider what would be required to decode this manuscript and reached the following conclusions:

- Determine the language used in writing the manuscript

- Correlate the Voynich alphabet with the modern English alphabet

- Decipher the code

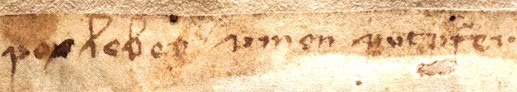

If Leonardo da Vinci was the author of the VM, he would have used the language of Dante, i.e. medieval Italian, so I have assumed the VM language to be Italian. I initially used Rene Zandbergen’s basic EVA characters(i) as a starting point to correlate the VM letters with the English alphabet, while taking into account that the Italian alphabet only uses 21 letters. Later in my studies I had to modify some of the EVA correlations. As the best code breakers, using powerful computers, were unable to decipher the code, it did not appear likely that I could break the code. I am however addicted of solving Jumbles and playing Text Twist and this made me consider a different approach. When I examined the VM script, I noticed that there were very few corrections, and the writing, though slow, had the appearance of easy fluidity. A complicated code would require making a preliminary copy using for example a slate for a scratch pad. Paper was expensive in the 15th century. To produce a 200 page manuscript under these conditions would be a very tedious task. The encoding must have been simple, easy and direct. Gordon Rugg(ii) has suggested that the VM is nothing but a meaningless jumble of letters! I wondered whether he was not correct, with one modification, only the individual words were jumbled, i.e. anagrams. I was further encouraged when looking at the last page, Folio 116v of the VM to find that the top line on this page is:

The Italian alphabet does not use the letter X. Leonardo used this letter as shorthand for ver.(iii) This line may be interpreted as follows:

The Italian alphabet does not use the letter X. Leonardo used this letter as shorthand for ver.(iii) This line may be interpreted as follows:

Povere leter rimon mist(e) ispero

Which translates into English as follows:

Plain letter reassemble mixed inspire

This brief sentence indicated that the use of anagrams should be investigated. This was further supported by reading Wikipedia’s report that anagrams were popular throughout Europe during the Middle Ages and that some 17th century astronomers, while engaged in verification of their discoveries, used anagrams to hide their ideas. Thus Galileo announced his discovery that Venus had phases like the Moon in the form of an anagram. Similarly Robert Hooke in 1660 first published Hooke’s Law in the form of an anagram.

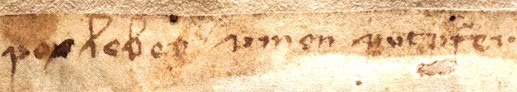

Word anagrams do not always offer a unique solution and an exact collelation between the EVA characters and the English alphabet has not been established, therefore, to test this ‘anagram hypothesis’ as precisely as possible, I used the single words found on many of the herbal pages. Most of these drawings are so poor that the author of the manuscript obviously considered it necessary to identify the roots/plants with names. I therefore used these single words to help modify the EVA alphabet (shown below) based on the plant/root name obtained from the subsequent translated Italian anagram. This resulted for the most part in a usable correspondence between the VM and English alphabets which when once established was used for deciphering all subsequent anagrams. I quibble a little here for at this time I have not been able to identify all the 21 letters of the VM Italian alphabet (j,k,w,x, and y excluded). The letters H, Q, Z and a single T have not been identified and there may also be some letter combinations like that used for tl that need to be identified. The ll combination may represent either one or two l’s. Letters like o and a, when they occur at the end of a word, have a tail and can easily be confused with a g, which has a curved tail. Other letters like m,n,r and u, when they occur at the end of a word have a curlicue. It is difficult to interpret words that have a number of c’s and e’s. These anagrams are best solved by trial and error. The letters I used from the VM and their English equivalent are shown in the table below:

Using this basic alphabet I have identified a number of plants, herbs and vegetables from the herbal pages. I was not able to decipher all the words, due no doubt to the fact that many of the plants around 500-plus years ago probably had common names that have since fallen into disuse. In addition modification in the spelling of some words may have occurred making it difficult for someone like myself, who does not read or speak Italian, to decipher these words.

Using this basic alphabet I have identified a number of plants, herbs and vegetables from the herbal pages. I was not able to decipher all the words, due no doubt to the fact that many of the plants around 500-plus years ago probably had common names that have since fallen into disuse. In addition modification in the spelling of some words may have occurred making it difficult for someone like myself, who does not read or speak Italian, to decipher these words.

Iused an Internet site, ‘Italian Anagram Dictionary,’ to help me unscramble the words and translate the anagrams into English. The book ‘The Botanical Gardens of Padua 1545-1995’(iv) helped identify some of the common names used for plants in Italy in the 16th century. You can judge from the examples given below, whether this Anagram Code has been successful deciphering this limited selection from the Voynich Manuscript. I hope some of you who read medieval Italian will help decipher more of the manuscript so we can finally learn the mysteries, if any, that this manuscript is hiding.

When I gave this manuscript a final reading, I suddenly remembered that Dan Brown in his book ‘The Da Vinci Code’ made use of anagrams. It will be ironic if Leonardo da Vinci is established as the author of the Voynich Manuscript and it is accepted that he used anagrams for his code. I doubt however that the Voynich Manuscript will have much to say about Mary Magdelene or the Priory of Sion, but that remains to be seen.

The pages that follow contain sections of the Voynich Manuscript with words that have been decoded using the anagram method. The first line of typed text above the Voynich handwritten text is the modern English interpretation of the letters. The second line is an Italian anagram of these letters. The third line is the anagram translated into English.

No comments:

Post a Comment